Featured

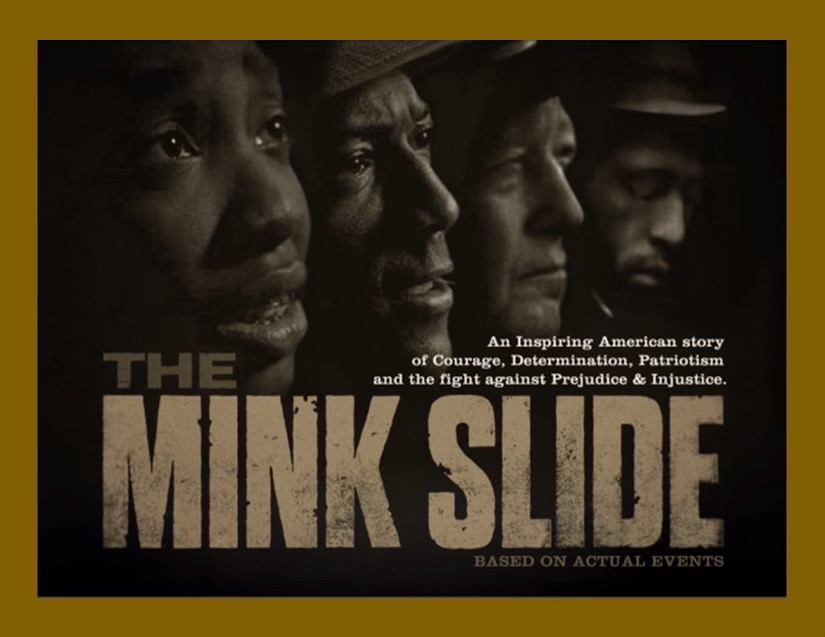

‘The Mink Slide’ tells how a mob planned to lynch Thurgood Marshall after he won a case for Black WWII vets

There is no dearth of courageous stories about African Americans overcoming odds. A St. Louis filmmaker has made a short film about a Tennessee injustice that involved 25 men and then-NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, who became the first African American Supreme Court Justice.

“Black World War II veterans took a stand and averted the lynching of a young Black Navy veteran and his mother,” said Owen Woodard. “A firefight took place where six people were shot including four police officers. The state of Tennessee charged 25 of the men with attempted murder. The NAACP was called and a legal team, including future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, was immediately dispatched to defend the men.

The movie “The Mink Slide” is set in 1946 in Columbia, Tennessee. The events surrounding the film occur in the years after Black soldiers returned from Europe where they experienced more freedom and respect as soldiers than they did at home in America. White Americans viewed the men as threats to the Jim Crow social order.

“There had been lynchings there before,” Woodard explained, “and the Black residents vowed that there would be no more social lynchings in their county again. Add to that, these men were fresh off the battlefields of the second World War and were determined to be treated with dignity and respect within their own homeland.”

When an all-white jury acquitted the men, some residents and the police kidnapped Thurgood Marshall.

According to Woodard, “If not for the quick and brave actions of his colleagues and the very men he defended in court, Thurgood Marshall would have perished in the swamps in Tennessee.”

Where the minks slide

The idea for the movie’s title came from the swampy area around the city where the Black neighborhoods and businesses were located. At night, white residents would dump their trash near the Duck River and the wild minks would scavenge through it and then “slide back into the swamps at sunrise.”

Woodard described his initial visit to the area where lynching victim, 20-year-old Cordie Cheek who attended Fisk University, had been found as “chilling.” Cheek was falsely accused of rape because a “treacherous” family did not want to pay him for some work he had done for them.

“I can’t imagine the horror of finding a loved one whose body was so mangled and desecrated and then knowing that the murderers will never be brought to justice. You can see why the Black residents were resolute in protecting themselves and one of their own.”

When Woodard heard about Marshall’s close call, he decided to make a movie. He went to Columbia to scout a location and was not welcome.

“At the time, we met resistance to us making the film period from some residents in Columbia, Tennessee, and we decided to film elsewhere, but a new mayor is in Columbia now, and he wants us to film it [the feature length] there. Chaz Molder is the current mayor, and he is thrilled to have us shoot the feature on location in Columbia.”

Woodard and his crew shot the trailer and the short in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and St. Louis.

He emphasized, “This was more of a concept film to show potential investors the timeliness of the project in hopes to expand it into a feature length film. We entered the short into a showcase, and it made a huge impression and people are excited about the upcoming feature.”

Woodard is raising capital to produce the move and said he has received cooperation from the Tennessee Film Commission.

Overcoming adversity

The years since he started the project have been challenging for Woodard. Illness struck, but he has forged ahead with his plans, calling on his ancestral resilience.

“Last year, I had the opportunity to visit the Wessyngton Plantation in Tennessee where my ancestors were enslaved,” he recalled. “I got to walk through the acres and acres of land that my ancestors had to cultivate. I pondered the back-breaking work they had to complete daily, and the horrible conditions that they had to endure. Still, many of them lived to be well into their 100s. Knowing that I have that kind of strength in my bloodline fuels my passion, and I want the world to know that all of us have descended from a strong and determined people who faced insurmountable odds and did so with dignity.”

As February draws to a close, Woodard sees no reason to stop talking about history – especially since it keeps repeating itself.

He said, “The fact that some 76 years later we still see people across the county in the streets protesting and shouting that ‘black lives matter’ is proof positive that we are still fighting that same fight.”

Woodard does have other little-known stories of triumph to share. But first, he is committed to finishing “The Mink Slide.”

“The more I learn about the events surrounding the uprising, the more determined I am to produce this movie,” he stated.

“The Mink Slide Salon: An Honest Discussion About Race, Violence and Justice” will be held at 6:30 p.m. Feb. 24 at The Missouri History Museum in St. Louis, Missouri.

Image Credits: Owen Woodard.

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’