Culture

The Georgia Man Behind Black History for the Rest of the Year

She was one of the first black teachers to enter the Fulton County school system during desegregation in Georgia. The white teachers treated her like an outcast and the white students called her the n-word. To many her name will never be known, but to one she’s an inspiration.

His mother was one of the reasons KuFunya Kail wanted to do a project that changed the way people celebrate Black History Month. The other is his father.

Born to parents who grew up during segregation, Kail understood that the struggle to overcome didn’t begin with one man or woman, but with millions; nor, did he come to realize, should the recognition and celebration of black history begin and end with one month.

So, he started “I Am My Own Black History,” a project that focuses on black people from all walks of life. Through videotaped interviews he captures their stories, the stories of who inspired them and the path they wish to pave for those behind them.

Kail wanted to recognize not just the heroes of the past, “but anyone who is adding to society,” he said.

“I wanted to celebrate us right now and what we’re doing to contribute to the future,” Kail, 41, said. “I wanted to celebrate janitors, lawyers, street sweepers, whoever you are because to me all of us are making contributions to celebrate each and every one of us as black people.”

Dr. William Boone, a political science professor at Clark Atlanta University, said it’s a worthwhile project. It’s drawing the “rank and file or ordinary folks into black history,” Boone said.

It teaches, “you don’t have to be extraordinary to be a part of black history.”

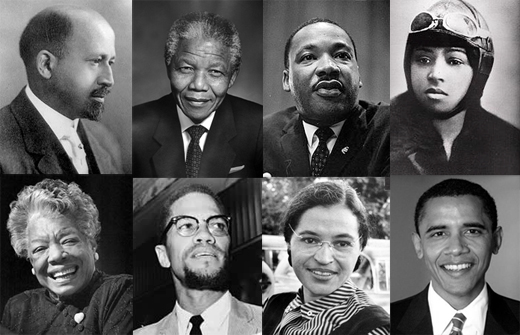

He said every Black History Month the standard names are trotted out such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks and Malcom X. “They are the result of thousands, millions, of black folks. They emerged as leaders, but they are not the ones who made black history,” Boone said.

Black history is celebrated across the world wherever you have black people. It ties them all together, giving black people a sense of pride in their entire race rather than just a couple of people, he said.

“It will tie people to their own history,” Boone said. “It moves you beyond the idea of thinking you must be a heroic figure to make a difference.”

Kail, a photographer and actor, said he had been thinking about what to do to celebrate Black History Month for a while. In the beginning, he only knew two things: He didn’t want to do something just for February and he wanted to do something uplifting. Then a few weeks before February began, he realized what he wanted to do.

He came up with the idea to do the interviews, which lasted an average of four minutes. In his East Point home, Kail created a studio and there he asked the participants three questions: Who inspired them? What word or phrase do they use the most? And what legacy do they want to leave behind?

“We are here for each other and we can inspire each other,” Kail said.

So far, he has interviewed 12 people including actors and an actress, a politician and professor, journalists and a geneticist. They are people he met on Facebook and on the streets, people he knows personally and professionally. People who saw what he was doing and decided to be a part of it. Their ages range from the mid-30s to upper 60s.

He plans to continue the project, adding at least one interview a week. He would like to interview middle and high schoolers, people in their 20s, black people from other countries. But one of the people he would like to interview the most is his mother.

His parents, who grew up in the 30s and 40s, have seen a lot of changes, Kail said. His father, who became a draftsman after serving in the military, died last year. His mother, who has retired from teaching, is still living.

“They didn’t accept things the way they were,” Kail said. “They made things the way they wanted it to be.”

When his mother entered the school, most of the black people there were cafeteria workers. When the white teachers attempted to get her to take their orders, she bristled. When they joined the students in calling her the n-word, she didn’t back down.

“I’m just here to do my job and to do it well,” she told them. And when the principal tried to fire her, she went above his head to ensure the security of her job.

In that environment, the sharecropper from Tifton, Ga. persevered and raised her children.

“She made me know anything was possible,” Kail said as did his father.

Charles Berkeley grew up in an abusive home, struggled in the New York foster care system and as a teenager spent days on the park bench not knowing where he would get his next meal. But, he held on to his character and taught Kail to do the same. He warned the younger Kail that he will face difficult times, but not to let the world change him.

But sometimes, it’s not easy to know what to do during a difficult situation as Kail recalled.

He was on the phone at the LaGrange Mall when someone screamed behind him, spitting on his neck. It was the night after Trayvon Martin’s murder in 2012 and tensions were high. Still, Kail thought it was a joke.

But that changed when he turned around to see a fuming security guard.

“’We don’t allow people to come in with gang colors,’” the man told him. Kail told him he wasn’t wearing gang colors. Still the guard insisted he leave the mall.

Kail refused. When the man appeared to reach for his gun, Kail reached for his phone and started recording.

“When he saw himself on camera, he turned blood red,” Kail said. The man backed off, but when Kail moved to another store he followed. Kail thought of making a stand.

“If I needed to do something to make sure my younger brothers are protected, I wanted to do so.” But from among the many onlookers, came the voice of a mother.

“Baby, please leave the mall. This isn’t worth it.” Kail left. He tried to tell his story to the media, to the mall management. But no one would listen.

For those who have a story to share, he’s found a way to help through “I Am My Own Black History.”

And like him, he discovered that for many of the participants, their “heroes are close to home.”

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’