HBCU

The Story of Greek Organizations on HBCU Campuses: Stepping Up to Support

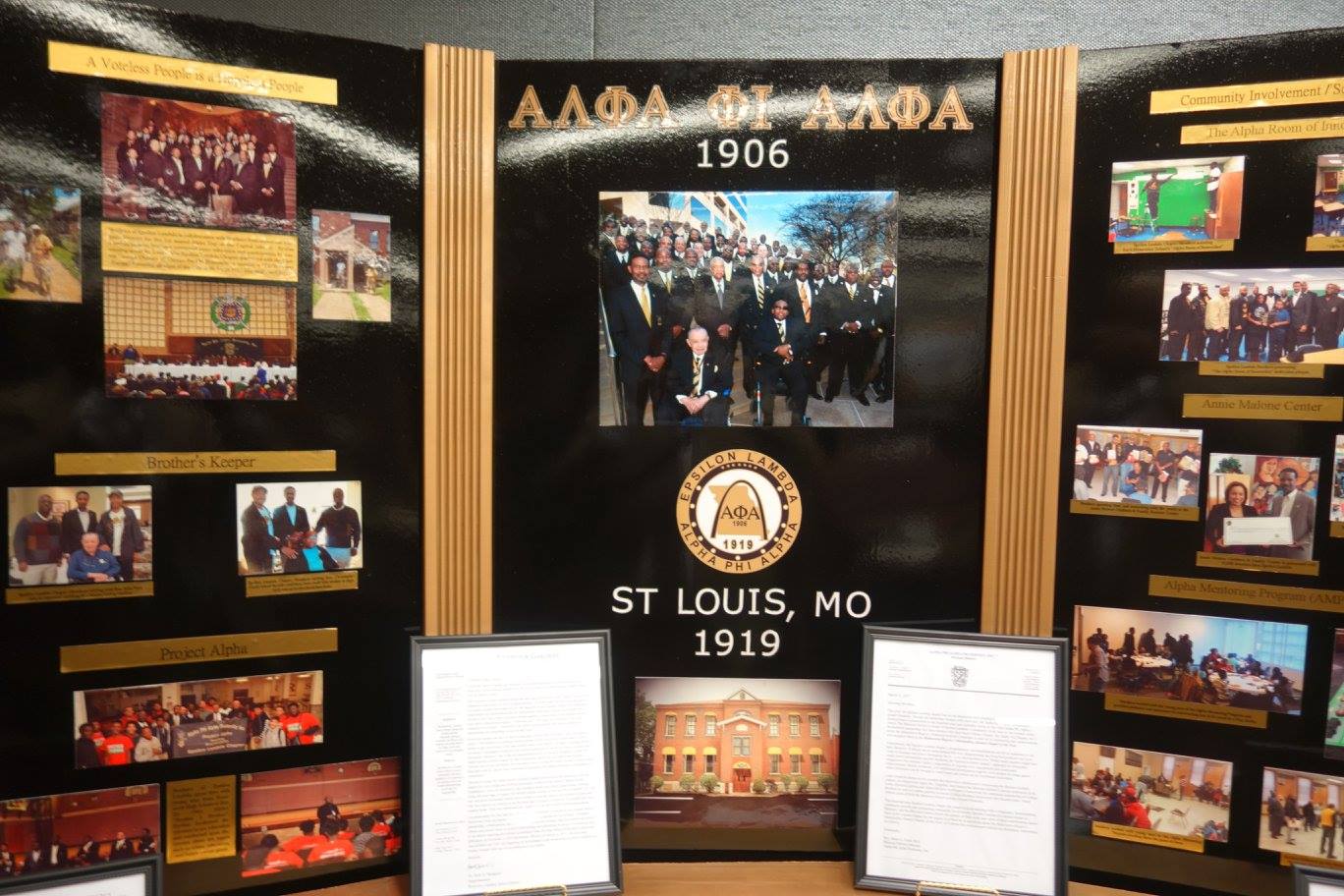

There were seven of them. Some were members of the Prince Hall Masons, a secret society, and others were the sons of members. It was a cold and stormy night on December 4, 1906 when they gathered in upstate New York. These black Cornell University students decided to create an organization that had no precedent.

And, they did so with opposition from their white counterparts on campus and in the community. They also had opposition from their own, said one of the founders, Nathaniel Murray, who shared some of their comments in an essay written by Andre’ McKenzie about the organization’s beginning.

“You will be the laughingstock of the town,” Murray recalled them saying.

“You cannot hope to do what white folks do.”

“You will lose your jobs as waiters if you try to imitate your employer.”

Still, they were determined. They started the first continuous African American intercollegiate fraternity in the nation, Alpha Phi Alpha.

Born in the shadows of slavery and the midst of Jim Crow, the organization would inspire the founding of other fraternities and the beginning of several sororities. In the end, there would be five fraternities and four sororities. They would become known as the Divine Nine.

The fraternities and sororities were the results of African Americans’ struggle for recognition and respect. Alienated from the white organizations, the members turned to each other for social intimacy, support and status. They became the black elites. They were leaders. They would protest against lynching, lobby for civil rights, and launch literacy campaigns. They would campaign for social reform, promote scholastic achievement and become icons of prestige among educated African Americans.

Each evolved to create their own calls and responses, brandings and tattoos, stepping and performances. They had their own symbols, colors and shields. But their requirements for new recruits were similar, such as volunteerism, a high GPA and a letter of recommendation. And they were connected by a single desire — the uplifting of the black race.

But, their organizations were shrouded in secrecy and despite their prestigious beginning, they have come under criticism by some of their own members for becoming nothing more than social clubs. And with incidents of hazing, partying and criminal activities haunting the organizations, many wonder if these black Greek-letter organizations are still relevant.

Black Greek Origins

For Carl Blunt, fraternities held no interest. He just wanted to get through college and that meant no interruptions, no affiliations. But later he met attorneys and political figures who he would come to admire. They were making a difference. They were at the forefront doing great things. They were the vanguards to social change for the black community and they were Omegas. He decided to join.

Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. was the first fraternity established on a black college. In 1911, three students and a faculty advisor started the fraternity at Howard University, a college that was originally created 150 years ago by white senators and congressman to educate their mulatto offspring, said Blunt, chairman of Omega’s International History and Archive Committee.

The second black fraternity, Kappa Alpha Psi, was started at Indiana University in 1911 by 10 black students, the only ones on campus. In 1922, a sorority, Sigma Gamma Rho, was formed at Butler University, then a teachers’ college. However, Howard University, the bastion of black education established in 1867 in Washington, D.C., became the cradle of black Greek-letter organizations.

From 1908 to 1920, five national organizations were established at the school including the now defunct Gamma Tau. There were two fraternities: Omega Psi Phi and Phi Beta Sigma (1914), and three sororities, Alpha Kappa Alpha (1908), Delta Sigma Theta (1913), and Zeta Phi Beta (1920). In 1963, Iota Phi Theta was founded at Morgan State University in Maryland.

From 1908 to 1920, five national organizations were established at the school including the now defunct Gamma Tau. There were two fraternities: Omega Psi Phi and Phi Beta Sigma (1914), and three sororities, Alpha Kappa Alpha (1908), Delta Sigma Theta (1913), and Zeta Phi Beta (1920). In 1963, Iota Phi Theta was founded at Morgan State University in Maryland.

The founders of the first eight black Greek-letter organizations were activists and scholars who were slightly more than one generation removed from slavery.

They began with a goal of uplifting the race, historian Dr. Maurice Hobson said. They understood the threats facing the black community and had to deal daily with racial aggression.

According to the book, “African American Fraternities and Sororities: The Legacy and the Vision,” they were likely mentored by adults who valued political, social and economic equity for black people. And, so all the organizations included service in their mission.

Secret Influences

The founders of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. held their first rituals in an Ithaca Masonic lodge. All the black Greek-letter organizations, whether conscious or unconscious, have their roots in African-influenced Masonic rituals and practices.

The founders of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. held their first rituals in an Ithaca Masonic lodge. All the black Greek-letter organizations, whether conscious or unconscious, have their roots in African-influenced Masonic rituals and practices.

Hobson, a member of Omega, said he knows of the connection between the organizations and the Masons, but none of the specifics. It is believed that their secret rituals, restrictive membership and focus on charity through community and public service were adopted from the Masons.

Hobson said the Greek-letter organizations also adopted the practices of black churches and benevolent societies as seen in the community service component of their organizations.

The calls, chants, call-and-response, ritualistic garb and performance styles that later became synonymous with Black Greek Letter Organizations (BGLOs) all had African antecedents.

“The survivors of the Middle Passage maintained them, and their children and grandchildren continued these practices within the sacred and secular institutions they founded and through the values they embraced,” according to African American Fraternities and Sororities.

“Starting off we were more like a secret society,” Blunt, 66, said. “We had certain questions to identify ourselves. There were certain things we said. There were certain responses.”

Like other fraternities, they had their own handshakes. They used certain words. When those words were placed in a sentence, people who heard them thought they were talking about one thing when they were talking about another, Blunt said.

“Everything on the shield meant something to us,” Blunt said. “Each symbol was a part of the secret that we hold dear to us. Where they are placed, each one has a meaning. It’s Omega’s secrets.”

Many of the founders were also members of the Mason.

“It’s something the founders did to complete the loop,” Blunt said. “They are Omegas and they are Masons.”

He said their secrecy existed for a reason.

“Educated black guys were going out to fight discrimination. They all could have gotten killed, gotten hung, thus the secrecy of our organizations,” Blunt said. “It’s how we protected each other, how we protected ourselves.”

Still, in the 1940s one of their members, an attorney, was assassinated, Blunt said.

Within a year of their founding, Alpha Phi Alpha began establishing new chapters, primarily at historically black colleges and universities. But, they also organized at the University of Toronto.

The other organizations followed suit, establishing chapters at other universities in other cities. Members could then continue their affiliation after their undergraduate days for the good of the race. They became the voice of protest against the pressures of segregation, discrimination, mistreatment and prejudice. They embraced and produced leaders such as the Father of Black History Carter G. Woodson, Civil Rights Leader Martin Luther King, Jr. and W.E.B. DuBois, one of the founders of the NAACP.

Still, the white national fraternities and sororities refused to recognize the black Greek-letter organizations. While all fraternities and sororities struggled for acceptance at college institutions, the black organizations also had to overcome discrimination from members of the faculty, other students and from white fraternities and sororities.

That isolation and alienation, which shadowed the lives of many black firsts on white college campuses, continued well into the 20th century. Under the weight of this alienation, some committed suicide and many dropped out of school. But with the black fraternity and sororities, they found a support system to help them socialize and survive. As more fraternities and sororities were formed, community service became a mechanism for racial uplift.

Sisters in the Struggle

Black sororities expanded during the time of the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camellia, and the Red Shirts. They flourished when violent mobs were using intimidation and murder to block black rights and preserve white rule. These hate groups’ tradition of night riding, assassinations, lynching and riots began in the late 1800s and continued well into the next century. Many blacks longed for a means of escape.

But, seven black women at Butler University had a different idea. Not only did they not run, they started a sorority about a block away from the world headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan in Indianapolis.

“They were of a different mindset. They were bold,” Deborah Catchings-Smith, the sorority’s president, said. They started Sigma Gamma Rho, the youngest of the four sororities of the Divine Nine, at a school that had about 10 black students each academic year.

They were under pressure to succeed in an environment that didn’t welcome their existence. But, they survived and seven years later had 500 chapters at universities across the nation.

They partnered with other organizations such as the NAACP. They worked with the few black officials in the legislature. They participated in marches and protests and community forums across the country.

But, they weren’t just fighting for civil rights. They were fighting for the survival of the black family along with some of their predecessors.

Omega Psi Phi was founded on the principles of manhood, scholarship, perseverance and uplift and those principles guided its members as they became involved in politics, civil rights and education.

Omega Psi Phi was founded on the principles of manhood, scholarship, perseverance and uplift and those principles guided its members as they became involved in politics, civil rights and education.

Hobson said Omega was formed during a time when a lot of black college students were being lynched. It was just before World War I and during the first wave of the Ku Klux Klan when there was a series of lynchings in D.C.

“They were lynching black college students for being uppity,” Hobson said.

So, the members learned self-defense, he said.

“A part of being an Omega man is being able to protect yourself and your community,” Hobson said. “You cannot walk into our community and harm our family.”

Decades later, the last of the Divine Nine would be formed.

For more than 50 years, four fraternities had symbolized the black collegiate Greek-life experience in America. Bu,t 12 students at Morgan State College (now Morgan State University), an historically black institution in Baltimore, MD, would change that with the forming of Iota Phi Theta on Sept. 19, 1963.

The founders were unique. Many of them were three to five years older than their peers and lived off campus. Some were military veterans and others were married with small children. And most of them were the first in their families to attend college.

“We fostered a love for each other because we were unique, because we were different,” one of the founders, Lonnie C. Spruill, Jr. said. “We didn’t come from college graduates, we came from the streets. That’s why we knew each other.”

They did the research to see if they should join one of the existing fraternities.

“We had formed such a bond between ourselves, we wanted to be together,” Spruill, 74, said. “There was so much going on with the struggle for civil rights.

“And we wanted to do our own thing. We wanted to build a reputation and not rest on one.”

There was a feeling among the group that, for the most part, the existing black fraternities, reflected a bygone era, one of the founders John Slade said, according to Andre’ McKenzie, who wrote In the Beginning. “An era when whites placed limits on black opportunities and blacks placed limits on their own aspirations.”

There was a need for change and they believed they could create an organization that would be receptive to a changing world.

“Building a Tradition, Not Resting upon One,” became their motto.

And one of their first acts was to participate in a march protesting segregationist practices at a local shopping center, McKenzie said.

Spruill said the fraternity wanted to be more community-aware.

“As we started, that’s all we did was to strengthen the community,” Spruill said. They mentored children, most of whom only had their mothers around. They led the effort for voter registration, feeding the homeless and worked in schools where they shadowed teachers and helped the students read. They have helped with the American Red Cross Sickle Cell program and participated in the annual St. Jude’s Walk to End Childhood Cancer.

Iota’s Grand Polaris Elect, or President, Andre Manson was a student at Virginia State University when some members of the fraternity reached out to him, but it was not to join their organization. One of them became his mentor, helping him with his classes.

“He had already graduated and came back to help,” Manson said. “Once I found out he was Iota, what his organization was about, what they do.” He decided to join.

“You did not feel like you were isolated. You did not feel that you were not welcome,” Manson, 49, said.

And that was the strength of the black Greek-letter organizations. Still, a problem would arise that would darken the reputation of these sororities and fraternities. And many would question their claims and purpose for being.

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’