Featured

How Electoral Justice Activists Have Changed The Political Landscape For Black Voters

If Democrats win control of the U.S. Senate—an outcome to be determined by the run-off election in Georgia on Wednesday —then electoral justice (EJ) campaigns will be key to this victory. EJ campaigns rely on the leadership of grassroots activists, including those on the frontlines of protests this past summer, to coordinate high-intensity Get-Out-the-Vote (GOTV) operations. Compared to high-dollar political consultants and party strategists, these activists are better equipped to mobilize hard-to-reach voters in communities plagued by political neglect, apathy, and voter suppression.

The presidential election in Georgia revealed the effectiveness and reach of EJ groups. Stacy Abrams’ Fair Fight, New Georgia Project, Albany Voters Coalition, and other groups that helped to defeat President Trump have been working overtime to turnout voters, especially Blacks, in the special election. Bernard Fraga and Cara Waite at Emory University found that Blacks are already outpacing other racial and ethnic groups in the Georgia run-off elections, making up one million of the three million votes cast from December 14th-31s

Fostering indigenous leaders and positioning them at the forefront of elections is a key objective of EJ groups. Whether these are older, Black women who have reputational standing in neighborhoods, formerly incarcerated persons working on reentry programs, or youth organizers leading protests, EJ campaigns prioritize community voices that are ignored by mainstream political strategists.

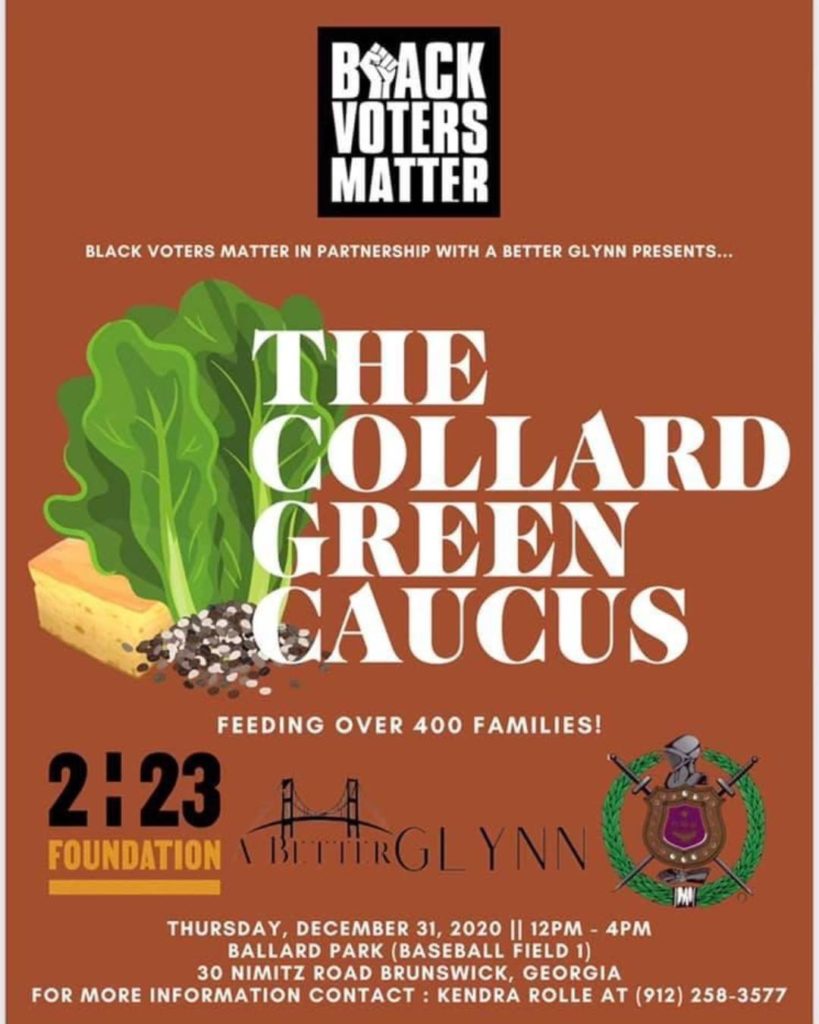

Many EJ activists honed their skills in non-electoral, community organizing campaigns. They activate hard-to-reach voters by using a repertoire of tactics such as phone banking, door-to-door canvassing, bus tours, protest marches, and celebratory demonstrations like dancing and concerts. Black Voters Matter Fund, Inc. even distributed collard greens— called the “collard green caucus”—to 30 counties in Georgia for New Year’s as part of its GOTV outreach.

The EJ History

EJ activism, interestingly, is an offshoot of the movement-building traditions of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in the 1960s and even the Southern Negro Youth Congress in the 1930s and 1940s. The Citizenship Education Program (also known as Citizenship Schools) in the late 1950s and 1960s, under the umbrella of the Highlander Folk School and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, is another predecessor to contemporary electoral justice campaigns. In the face of racial terrorism, these groups organized freedom votes, youth legislatures, anti-poll tax committees, voter education workshops, and voter registration drives.

Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, however, ignited a new wave of EJ activism. In 2017, Black Voters Matter Fund, Inc. collaborated with three dozen groups in Alabama’s special election to help Doug Jones win the Senate race. A year later, the Movement for Black Lives Matter’s Electoral Justice Project recruited grassroots activists, many from the frontlines of criminal justice and police reform movements. The project paired them with electoral justice campaigns across the South.

In the 2018 and 2020, organizations such as Black Leaders Organizing Communities in Milwaukee and Mobilize Detroit activated voters in Rustbelt states. The Workers Party invested in grassroots organizations throughout the U.S. South. The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, Free Hearts in Tennessee, and Voice Of The Experienced in Louisiana led voter outreach in high-incarcerated communities, and in some cases, registered voters in pre-trial detention. Southerners On New Ground has trained LGBTQ+ non-White activists in electioneering tactics.

Latinx, Asian, and Native American groups have also adopted EJ models of organizing. The National Korean American Service & Education Consortium and the Woori Center mobilized 189,000 Asian-American voters in Pennsylvania. Four Directions, Inc., the Rural Arizona Project and other Native American groups organized GOTV operations in Arizona’s Navajo Nation. Voto Latino, Mijente’s FueraTrump campaign, and Mi Familia Vota targeted Latinx voters in 14 states.

Although EJ work has been years in the making, prior to the 2020 election, the media gave more attention to the Justice Democrats allied with Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and other newly-elected progressives. Certainly, there is overlap between the Justice Democrats and electoral justice organizations. Yet, EJ activists are much more embedded in ‘Red States’ especially in the South, where conservatives and voter suppression regimes have a decided advantage.

Beyond Georgia

Regardless of what happens in Georgia, EJ campaigns may be here to stay due to decades-long transformations of the media and party system. The explosion of social media and cable television, along with partisan dealignment and candidate-centered elections since the 1970s, have allowed both progressives to run parallel campaigns detached from top-down, party organizations. Trump’s election and the Tea Party’s rise a decade ago show that even right-wing politics have been influenced by parallel campaigns.

For grassroots resistance movements and Black politics, EJ networks will be increasingly necessary to activate voters living in communities suffering from low-wealth and economic distress. Black communities have been destabilized by the expansion of the carceral state, gentrification, foreclosures, and displacement caused by natural disasters. Voter suppression backed by federal court decisions that have weakened the Voting Rights Act, along with a firehose of disinformation on social media intended to discourage Blacks from voting, continue to present barriers to political engagement.

Groups that can energize Blacks and other voters of color, notwithstanding these barriers, will be instrumental to winning competitive elections. This test will be put on display in Georgia’s run-off elections, as well as future election cycles.

Dr. Sekou Franklin is a political science professor at Middle Tennessee State. He is the author of After the Rebellion: Black Youth, Social Movement Activism and The Post-Civil Rights Generation.

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’