Culture

Can We Talk About Race?

In the most well-known pocket of affluence in the St. Louis area, there is a robust conversation underway about race. It started days after a white police officer shot and killed Michael Brown. Almost six months later, the dialogue in Ladue is adding voices and opening minds.

“It really resonated with Megan and me. We both felt strongly about the injustice that was done to Michael Brown, his family, and his community. We wanted to do something, ” says Lynn DeLearie.

DeLearie and Megan Frank readily agree that they are not the most obvious candidates for civil rights activism. Both are white, in their 40’s, and not inclined to “join a protest, carrying a sign.” But these two mothers, who met when their daughters were kindergarten classmates seven years ago, have started a group called Ladue Change Agents for Racial Equity or LadueCAREs.

Frank says, “We get hung up on how to talk about race so we don’t talk about it. Our kids are more comfortable having the conversation, and we need to be aware of how we’re modeling for them.”

Motivated by their anger and frustration following the fatal shooting of Brown, the two met and decided to take action. Frank read an article about her high school principal who was “intentional about bringing black and white people into his home to have candid conversations about race.” She and DeLearie called Franklin McCallie, who now lives in Chattanooga, and he urged them to start talking.

Both women rounded up their considerable contact lists and began reaching out. Frank is the owner of an advertising agency, and DeLearie works in fundraising with non-profit organizations and recently at De La Salle Middle School, located in the historic African American neighborhood known as the The Ville. They used their combined clout and creativity to bring a group of blacks and whites together to talk about the shooting.

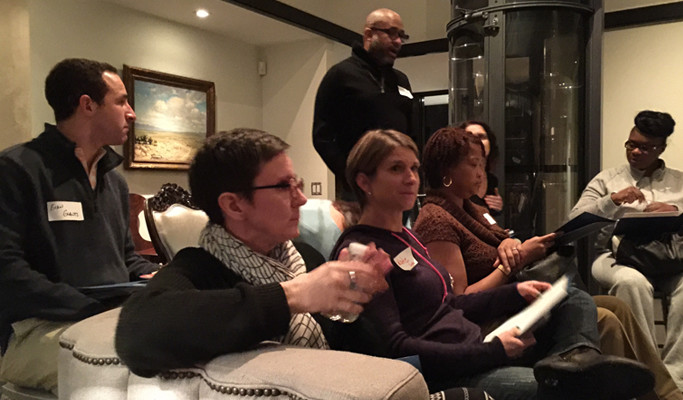

The first meeting occurred before the grand jury decided not to indict the officer who killed Brown. They met at Frank’s home where the group watched the movie, “White Like Me: Race, Racism and White Privilege in America“, to jump start the conversation. They describe the evening as “amazing.”

DeLearie adds, “You would have thought we had known each other. There was a lot of vulnerability.”

Frank concurs, adding the caveat that both went into the meeting understanding there could be barriers to an authentic discussion about such an emotionally charged issue. “I may not be completely aware, but I know what white privilege is. Now that I see the injustice, it is irresponsible of me not to do anything about it,” she says.

The meetings are “very productive” says Erick Falconer, one of the African American members of LadueCAREs. “What keeps us coming together is trying to find a way to improve the environment for our children…to buffer our children so they don’t grow up in an area polluted by things that have happened historically and a lot of things they don’t really understand,” he states.

Falconer is the father of two sons, ages eight and 12. He says, “Lately, we have come together to see what we can do to foster healing and educate each other about what creates this proliferation of separation.”

LadueCAREs meets the second Monday of the month. Frank and LeDearie say there has been a “different dynamic” each time. The group addresses only the relationship between blacks and whites, expressing a desire to “be effective, but we can’t do everything.”

They have harnessed their influence and count the school district among LadueCAREs’ supporters. “A lot of this is at a policy level…judicial and educational,” DeLearie says. “People in this school district know a lot of people uniquely positioned to educate, raise awareness and influence people.”

Vincent Flewellen, an African American teacher at Ladue Middle School says, “It’s great that families of privilege…in class and race…are having these difficult conversations of racial inequities and working to become active agents of change by using their privileges and voice.” Flewellen told Dr. Tiffany Taylor-Johnson who is also African American and the 7th grade associate principal at the middle school about the group.

Taylor-Johnson speaks excitedly about the meetings which foster “comfortable discussions.” She underscores that “conversations about diversity and race can be challenging, but this group has done an outstanding job facilitating meaningful dialogue in ways that I am certain will make a difference.”

In the coming months, Frank and DeLearie plan to engage the broader community. They are looking for ways to move the conversation past just talk. But, talk is often the gateway to progress.

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’