Featured

Black Women: Motivated Savers and Financial Strategists After The Civil War

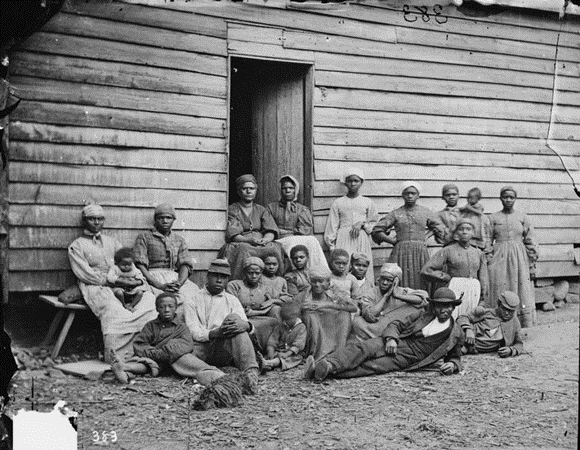

The transformation from slavery to free labor after the Civil War influenced the various strategies Black women pursued and contested in their search for economic security. The “free” in free labor did not mean the opposite of slavery nor did it mean that Blacks were, as historian Willie Lee Rose notes, “free to do just as they pleased.” Black people’s labor remained essential to revitalizing the Southern economy and to maintaining the United States’ predominance in the global economy. To put it plainly: Northern military officers, philanthropists, and politicians needed Black people to work. But they seldom described free labor in terms of their own bald economic need. They preferred instead to imagine they offered Blacks a path to prove Blacks’ fitness for citizenship through demonstrating their economic responsibility. During the war, officers, philanthropists, and politicians experimented with programs that combined some form of paid wage labor with various savings schemes. Their key experiments included the Freedmen’s Fund and free labor and military savings banks and culminated in the creation of the Freedman’s Bank in 1865. These experiments undermined much of the economic autonomy Black women struggled to carve out after the Civil War, leading them to question the essential differences between the slavery and freedom.

Freedmen’s Funds

A Union general at Fortress Monroe created the first Freedmen’s Fund in 1861 to care for Blacks who had escaped enslavement and fled to the Union lines for protection. In the early months of the war, the federal government did not have a formal policy for dealing with the hundreds then thousands of Black escaped slaves who sought refuge behind Union lines. Some generals returned escaped people to their owners. General Benjamin Butler at Fortress Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, however, welcomed Blacks as contraband of war. He figured that the contrabands, as the Black men, women, and children were called, helped the Union in two ways. First, they could help the Union by working, building fortifications, nursing wounded soldiers, and doing other work for the Army. Second, they could hurt the Confederates by depriving enslavers of their primary sources of labor and wealth. The military gave Blacks little choice in the matter. In October 1861, the new commander of Fortress Monroe issued an order establishing a mandatory work policy. The Army would pay Blacks wages, but a portion of their wages would be set aside in a fund to care for those who could not work, such as children, the infirm, and the elderly.

Other Army leaders created similar Freedmen’s Funds. Some created funds that kept all of Black people’s wages and used their wages to buy blankets, food, and clothing for all Blacks in the camps. Soldiers also confiscated horses, wagons, money, and other valuables Blacks brought with them to the Union lines. What soldiers and the Army officials did not steal for themselves, they placed in the Fund.

These Funds exploited more than they helped freed people. Military officials created the Funds because they assumed Black people had to be taught the value of work and a dollar. There they made two mistakes. Black people had worked for hundreds of years building the wealth of the country. Nor were Blacks unbanked. They were conversant with the market economy. Enslaved people saved money they earned from overwork, hiring themselves out, and independent economic activities like selling foodstuffs in brick-and-mortar banks, with local merchants, and with their enslavers. Enslaved people also created financial institutions in which they saved money, such as secret mutual aid societies. With the Funds, however, Blacks had no individual access to their money. They had no say in how their wages would be used. Blacks were not quiet about the situation. They complained bitterly to missionaries, politicians, and other military officials.

As the war progressed, some military leaders tried to reform the Funds and allow Blacks more autonomy over their money. Rather than a central fund, they created at least three freestanding banks not only for Black workers but also Black soldiers. General Nathaniel Banks created the first free labor and military bank in New Orleans in early 1864. General Benjamin Butler opened a bank in Norfolk soon after, and General Rufus Saxton followed suit in Beaufort, South Carolina. The banks offered distinct advantages over the Funds. Workers could decide for themselves how much to save. Army Quartermasters issued passbooks so workers had a record of their deposits. But the banks were not perfect. The accounts did not earn interest. As with the Funds, some soldiers and officials working for the banks embezzled freed people’s savings. Ultimately, these banking experiments preserved an ideological commitment to Black subservience. They left most Blacks economically vulnerable with little in the way of civil or political rights.

The experiments also ignored the challenges its women depositors faced. Few records have been found, but Black women probably contributed significantly to the Freedmen’s Funds and used the free labor banks, though in a limited way. Black women should have counted among free labor banks’ most active users for three reasons. First, savings banks were extremely popular with women. The self-made-man mythology so popular in the late 19th century obscures women as the main depositors in savings banks. Second, Black women earned money. The Army could not spare many able-bodied men for agricultural work. Freedwomen and girls made up the primary labor force on most leased and confiscated plantations. They also earned wages working as nurses, cooks, and in other capacities. Finally, enterprising women earned money on the side selling goods and services to soldiers.

Black women needed safe places to place their wages and profits, but they felt uncomfortable placing their hard-earned money under the supervision of people who demanded they only earn money from sources and activities the military approved, arranged, and supervised. The Army paid women below-market wages and sometimes forced them to work in dangerous conditions. On isolated rural plantations, Black women were vulnerable to Confederate raids. Whites who leased the plantations sometimes treated the women as slaves. They forced the women to work, withheld wages (if the women were even paid at all), and subjected women to both physical and sexual violence.

Women met banking and savings experiments during and after the Civil War with mixed emotions. Reformers, military officials, and former enslavers whose plantations were returned after the war wanted to extract as much labor out of Black workers as they could, but they seldom respected their rights as free workers. Whites interpreted Black women’s efforts to exert more control over their working conditions and their demands to be paid fair wages as threats to whites’ authority. Whites sometimes framed Black women’s protests and demands as further evidence that Blacks were lazy, ignorant, and unprepared for full citizenship rights. For Black women in particular, these experiments, sitting at the uncomfortable juncture of labor and ideology, coerced Black women to work but placed them outside considerations of proper, respectable womanhood for doing so.

For Black women, being free meant acting free. They resisted being commodified as ticks on a ledger where only other people profited. Black women openly protested, slowed down their work, and organized strikes. They also continued to save and invest their money in financial institutions that they controlled, especially in the church and secret societies. Through these actions, they not only asserted their rights but also affirmed their economic importance to the U.S. economy.

If the truth is told, Black women did not achieve their vision of freedom, even with the opening of the Freedman’s Bank in 1865. Few received land. They did not even get the right to vote with passage of the 15th Amendment. They stood, however, squarely at the center of whites’ vision of the reconstructed fields, factories, and households of the South. Black women’s actions changed few official policies, and it was evident that the free market would not make Blacks and whites equal. Black women’s resistance did reveal, however, that they would not allow those in charge of these banking experiments to ignore the moral dilemmas inherent in their policies and actions. Black women’s activism in the 20th century, from demands for Civil War widow’s and ex-slave pensions to washerwomen strikes to streetcar boycotts to boycotts and sit-ins, reveals that they never gave up on their freedom dreams.

Dr. Shenette Garrett-Scott is an associate professor of history and African American Studies at the University of Mississippi and author of Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance to the New Deal. Follow her on Twitter at @EbonRebel.

-

Featured12 months ago

Featured12 months agoArkansas Sheriff Who Approved Netflix Series Says He Stayed ‘In His Lane’

-

HBCUS12 months ago

HBCUS12 months agoSenator Boozman Delivers $15 Million to Construct New UAPB Nursing Building

-

News12 months ago

News12 months agoMillions In the Path of The Total Solar Eclipse Witnessed Highly Anticipated Celestial Display

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates