Black History

Black History Lost and Found: New Research Pieces Together the Life of Prominent Texas Surgeon and Activist

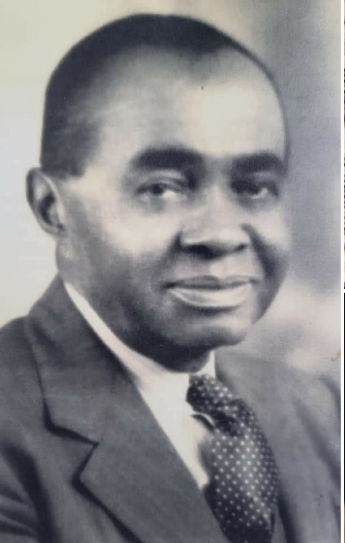

In the 1930’s and 40’s, Dr. William Marcellus Drake was considered a “civic giant” in Houston, Texas. Decades after his death, even his descendants knew little about his story. It turns out that Dr. Drake, who talked little about himself, left plenty of clues about his journey from a young farm hand in Mississippi to surgeon and fighter for racial justice in Texas. Thanks to the digital age, we are finally learning his full story.

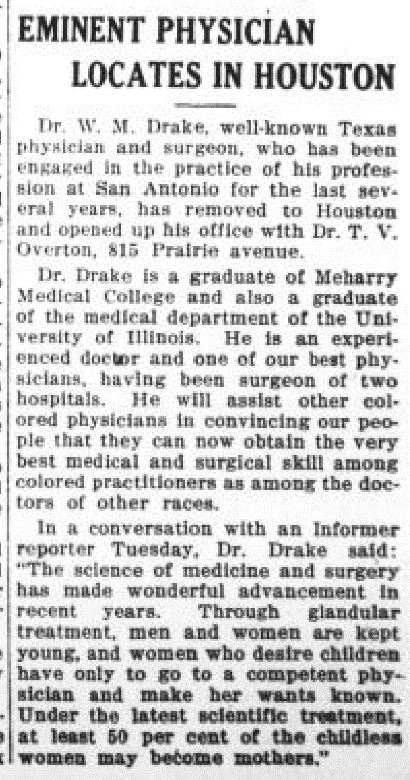

A century ago, a small item appeared on the front page of The Houston Informer, the city’s Black newspaper. It was a brief, three-paragraph announcement that officially introduced Dr. William Marcellus Drake to the city of Houston, Texas, with the headline: Eminent Physician Locates In Houston.

December 1923 was the beginning of a new chapter for Dr. Drake, a gifted and well-known surgeon, activist and philanthropist. His first wife, Bessie M Brantley Drake, died three years earlier in their hometown of San Antonio. Their only child Wilhelmina was a teenager. Dr. Drake was 53 years old and had already spent 30 years as an educator, physician and activist, expanding schools, building hospitals and fighting for racial justice.

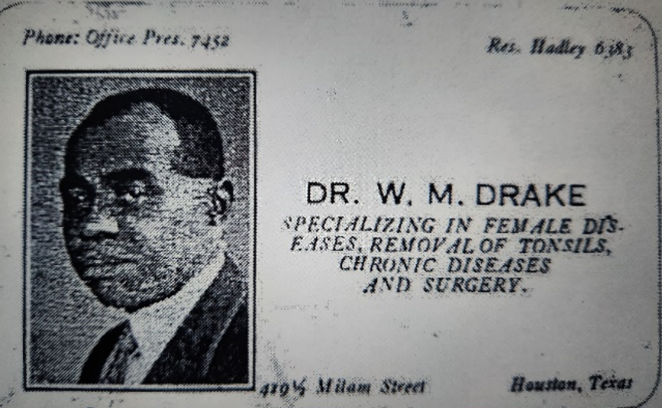

Dr. Drake earned two medical degrees and was performing major surgeries in an era when Black people were turned away from hospitals or subjected to inferior care in the segregated basement wards of public hospitals. Black women benefited from his specialty in removing fibroid tumors.

“The science of medicine and surgery has made wonderful advancement in recent years,” he told the Informer in 1923. “Under the latest scientific treatment at least 50 percent of the childless women can become mothers,” he said.

Dr. Drake’s influence extended beyond medicine. In San Antonio, he was a founding member of the city’s N.A.A.C.P. chapter – one of the largest in America at the time. In Houston, he would make a name for himself by standing up against lynchings and filing lawsuits against racist all-White primary election laws that prevented Blacks from exercising their right to vote.

Despite a busy medical practice in Houston, and a hectic schedule of surgeries and civic commitments, Dr. Drake still had time for his family and new wife, Inez Taylor Drake, a registered nurse from Buda, Texas. The couple raised three children in Houston’s Third Ward, William Jr., who died at age eight after contracting polio; George, who followed in his father’s footsteps as a physician; and his youngest daughter, Evelyn Drake Houston, family historian, now 88 and living in Kansas City.

Evelyn remembers riding the merry-go-round with her father. At after-school recitals, she would look out into the audience and find her Daddy had arrived on time – sitting next to her mother. “He was always there,” she said.

Eventually, Dr. Drake’s remarkable record as a physician and community leader would be celebrated with a Man of the Year award. “Easily one of the most unselfish citizens of Houston without regard to color,” wrote the Houston Informer in 1939.

After a long and distinguished career, Dr. Drake died of a heart attack at the age of 78 on August 21, 1948. His daughter Evelyn held onto photographs and memories, but she says he did not talk about himself or his upbringing. She only knew the names of his parents and the name of the town where he was born – Egypt, Mississippi. Even the names of his siblings would remain a mystery until many years later. For 50 years after his death, the narrative of his work and sacrifices was scattered among various documents, letters and biographical sketches. It would take a digital revolution to stitch things back together.

In the late 1990’s, the internet and digital archival tools emerged as a pathway to reconstruct Dr. Drake’s life. Correspondence, census data, research papers and newspaper articles hidden from plain sight began finding their way onto the internet. The growth of searchable databases are providing clues to the lives of historical figures like Dr. Drake – answering questions that Drake’s daughter was too young to ask.

Early Influences

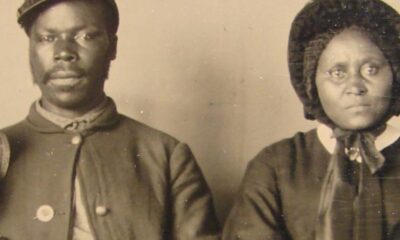

Chief among those questions is this: How did the son of formerly enslaved people make it from a farm in Egypt, Mississippi to the position as one of the most respected civic leaders of his generation? The answer lies, in part, with his upbringing according to a recently discovered newspaper profile.

Dr. Drake’s father, Rev. George Washington Drake, was a “pioneer in the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mississippi”, as reported by the May 11, 1911, edition of the Southwestern Christian Advocate. Rev. G.W. Drake and his wife Sarah Jane Barney raised five children from slavery through the Civil War and into the Reconstruction era. Robert, 22; George Jr., 21; and Bettie, 16; were all listed in the 1880 census as schoolteachers. Dr. Drake – the youngest, is listed as 10-year-old “Willie”- and his sister Alice, 14, were farmhands. It is no surprise that church and education would play a critical role in his life. In fact, Dr. Drake would attend three schools that were all supported by the Methodist Episcopal Church: Rust College in Holly Springs, Mississippi; Wiley College located in Marshall, Texas; and Nashville’s Meharry Medical College.

A Gifted Communicator

In 1911, Dr. Drake stood in front of 3,000 White and Black people in San Antonio. It was the first day of famed educator Booker T. Washington’s whistlestop tour across Texas aimed at improving race relations. Dr. Drake was selected to introduce Washington, declaring “Few Americans made such an impression upon public opinion, removed so many prejudices and awakened greater helpfulness in relation to the solution of a problem.” The audience was moved. Washington rose from his seat to a thunderous applause. Dr. Drake’s words were published in newspapers across the country.

This was just one example of Dr. Drake’s persuasive and oratorical talent. Throughout his career, he would be called on to deliver speeches and serve as master of ceremonies. Keep in mind, he was the son of a minister and was comfortable in front of an audience. As for his connection to Booker T. Washington, recent research has uncovered his service as a delegate to the National Negro Business League Convention in 1901, an organization founded by Washington.

A Leader in Medicine

In the 1920’s Dr. Drake was one of the most vocal physicians at the newly constructed Houston Negro Hospital (later known as Riverside General). His correspondence archived at the University of Houston reveals a man determined to see the hospital succeed, even if that meant going against the wishes of his friends who wanted to boycott the hospital amid an on-going dispute over leadership.

It turns out that Dr. Drake was intimately knowledgeable about hospital operations 20 years prior to that hospital fight. A newly discovered profile published in 1908 of the Southwestern Christian Advocate notes Dr. Drake poured his own earnings into a renovation project, adding a second floor to a frame house to establish the 10-bed Wiley University Hospital. Dr. Drake was named chief surgeon.

A Prolific Fundraiser

Some of Dr. Drake’s most impactful work was his civic activism. His persuasive talents and integrity made him a frequent choice to head fundraising efforts to support churches, hospitals and the fight for racial justice including the case against Bob White, a Black man facing a bogus rape charge. When the Supreme Court failed to uphold his conviction based on lack of evidence, White was murdered – shot to death- inside the courtroom during a third re-trial. Dr. Drake was a fundraiser for the Bob White legal defense.

Additional research has uncovered a pattern of Dr. Drake’s courage to stand up against lynchings. He was a founding member of the San Antonio N.A.A.C.P chapter in 1918 and he was among a contingency of Black community leaders who encouraged editors of the White San Antonio newspaper to take a stronger stance as the wave of violence made headlines across the country.

A Defining Legacy

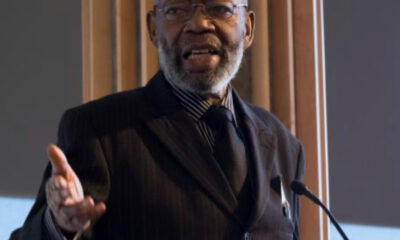

Dr. W.M. Drake attending 1947 National Medical Association Conference, Los Angeles, CA

It’s impossible to know if anyone could have predicted the impact of Dr. Drake’s arrival in Houston in 1923. Clearly, his reputation preceded him, but his forward-thinking philosophy left little room for self-reflection. While Dr. Drake may not have been thinking about his own legacy, his contemporaries understood his “permanent place in the hall of civic giants.” In 1944, Dr. Drake was awarded Man of the Year by the Houston Negro Chamber of Commerce. The recognition included this summary of his commitment to improve life for Black people in America:

“Dr. Drake’s leadership in the community has been safe, sound and conservative. His work in the church in the Houston Negro Chamber of Commerce, Y.M.C.A and N.A.A.C.P is very commendable. He has built his work and his career upon a rock – not sand – and his record will stand the mighty roars and sweeps of the gales.”

Carlton Houston is a former journalist, family historian and grandson of Dr. Drake.

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’