7 Summer Sites

Atlanta’s Apex Museum: A Treasure Trove of True Untold Stories for African Americans

In what used to be a tire company on a street once known as “The Richest Negro Street in the World” exists a little-known treasure— at least to many African Americans who have lived in Atlanta for decades.

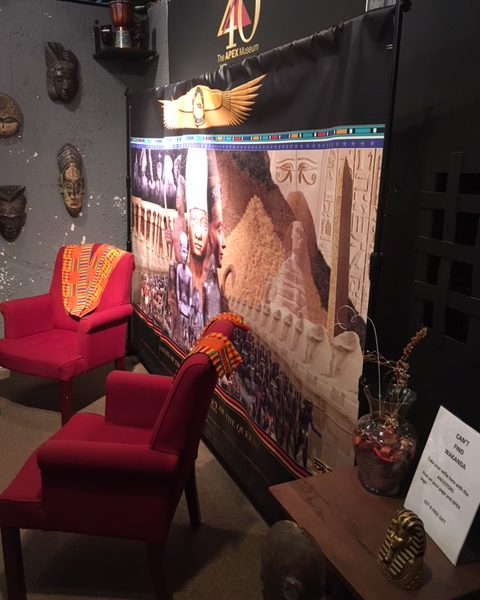

It’s the first of its kind in Atlanta and existed long before museums and memorials were dedicated to the African American experience. As of May, it’s been around for 40 years. Yet the Apex museum on Auburn Avenue is struggling to keep its doors open. Some say it’s the result of a community that doesn’t cherish its own.

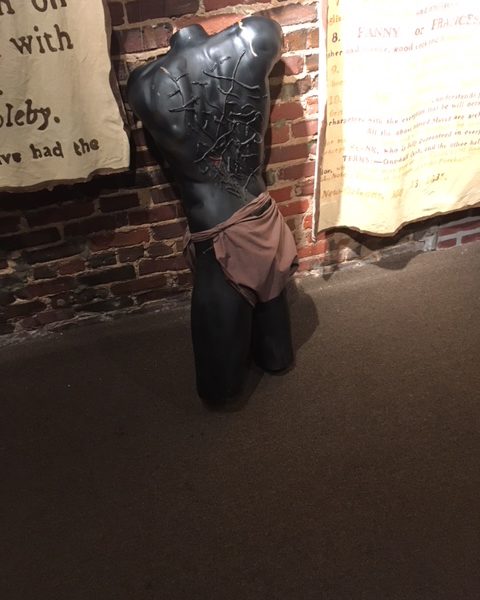

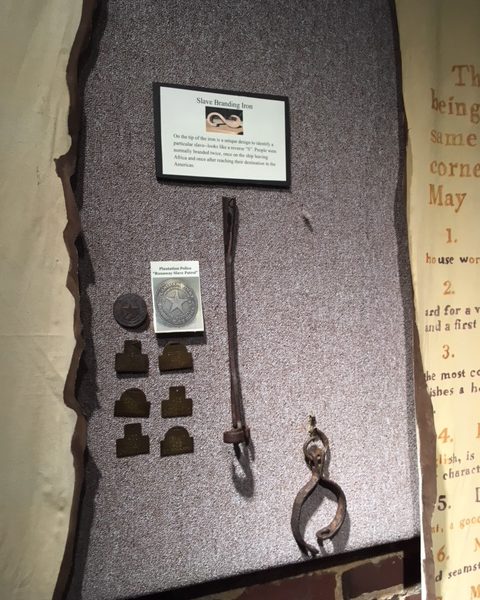

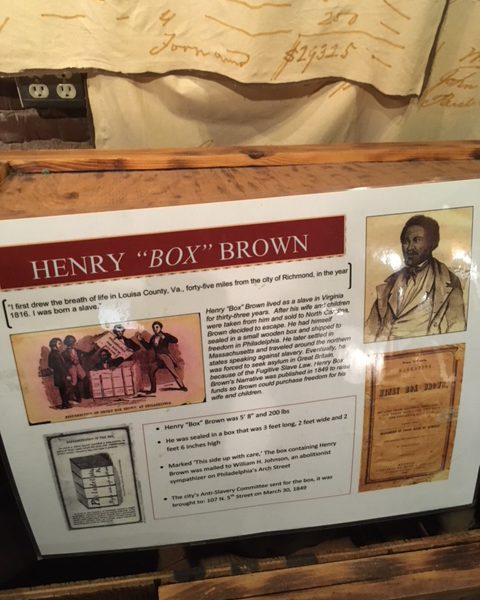

Inside it tells the story of black people’s past that began before slavery. It tells of a generation of kings and queens who once ruled the regions of Africa. It then journeys through the slave trade and arrives at the present with narratives of black men, some of them former slaves, who built empires and of women whose work contributed to stem cell research.

But, its decline tells a different story. And its founder and president, Dan Moore, is left to wonder, “How former slaves can build an empire that free slaves cannot maintain?”

Moore moved to Atlanta in 1974 to open a film studio when he saw the need for a museum that would document African Americans’ story.

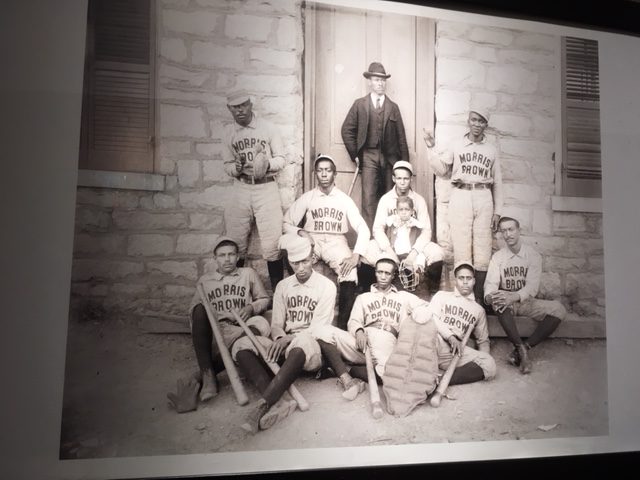

“I’m a filmmaker, but when I see a need I step in and make it happen,” Moore said. And so, he did. From a collector, he bought African masks and artifacts, which became the museum’s first exhibit. And, Morris Brown College provided a building to showcase the collection.

Later a board member found a tire warehouse, and with the help of a Bank South employee, they received a $2.3 million loan to buy the building and renovate it. Their first tour group was Morris Brown students.

When the Southern Education Foundation, which had bought the second floor, moved last year the Apex board members attempted to get another loan to buy it back. But the bank they were dealing with chose to sell it to a white developer.

“It’s white colonialism under a new guise, which is called gentrification,” Moore said.

And it’s reflected, not only at the museum, but in the decline of the area, which once housed some of the wealthiest black-owned companies in the world, he said. From builders to bankers and opthamologists to pharmacists, the community was booming. A former slave, Alono Herndonz, established a commercial building that housed the offices of many of these businesses. Herndon, one of the first African American millionaires, also started Atlanta Life, which became the second largest black-owned insurance company in the country, Moore said.

“It was a thriving community because blacks had to come together and build their own because they were not allowed in the white community,” Moore said. “As soon as the walls of segregation began to fall, blacks abandoned Auburn and this is where we are today.”

Though he’s surrounded by their images and stories almost daily, Moore said he can’t help but think of what enslaved black people went through and how little is being done to honor their memory and their struggles.

Still, there are those who continue to dig for truth, for their story. And they, sooner or later, find their way to Apex. Between 35,000 to 40,000 people from every state and about 50 countries visit Apex each year, Moore said.

One Wednesday afternoon, a mother came in to tour the museum with her teenage daughter and young son. They were taken to the display done by Michelle Mitchell called The Untold Story, which tells the stories of blacks before they became enslaved.

Her teacher, Asa G. Hilliard, had told her, “’Whatever you do, never let them begin our history with slavery,’” Moore said.

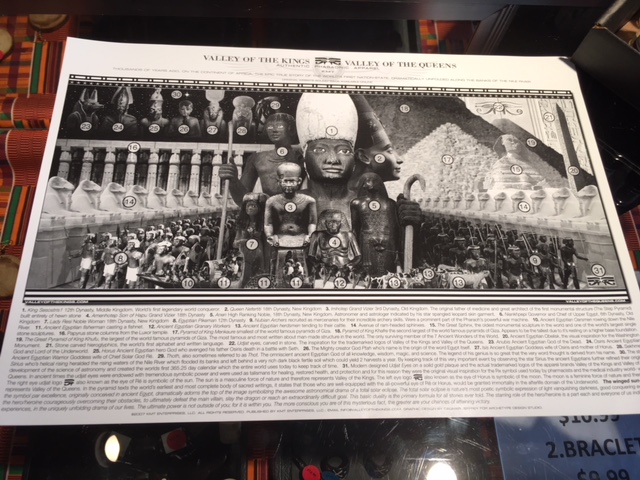

So, she started it from 6,000 B.C. in Egypt where black people were once rulers and she continued onto Emperor Haile Selassie, the 111th descendant of King Solomon and Queen Sheba, who is credited with modernizing Ethiopia and pushing for Africans unity. Then there was Menelik II who led one of the most successful campaigns of Africa resistance to European colonization.

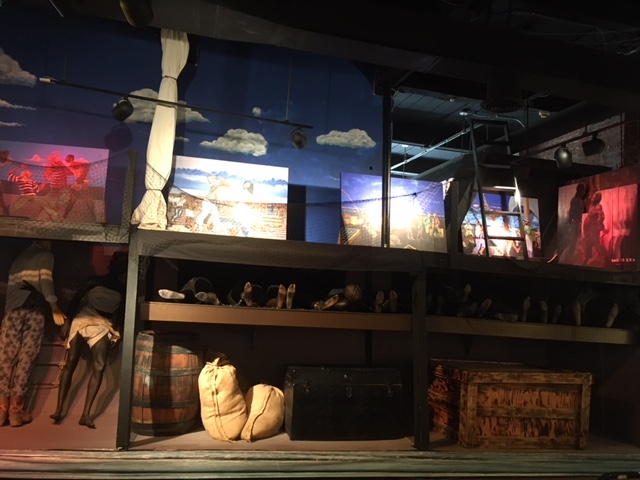

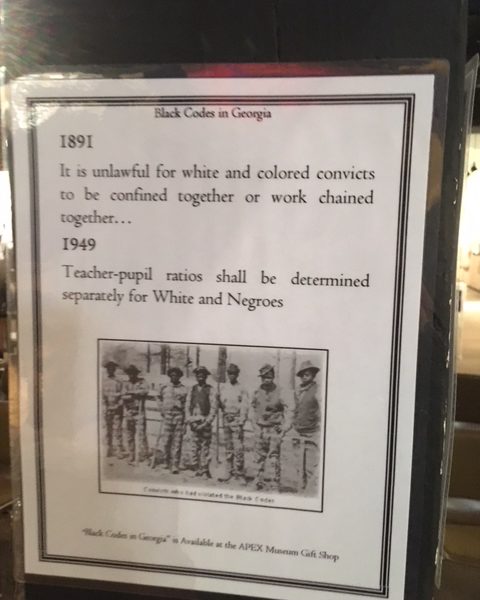

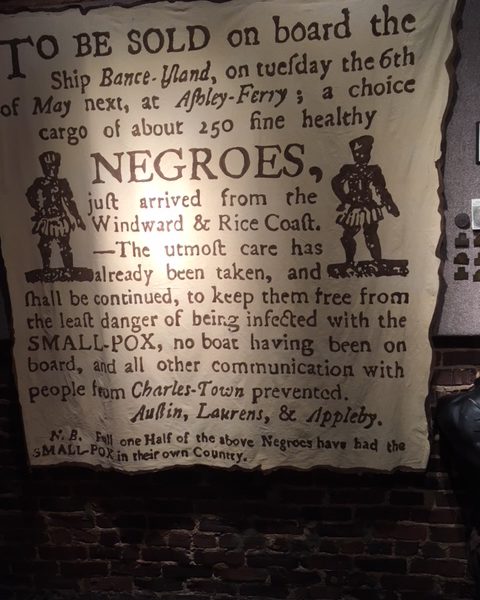

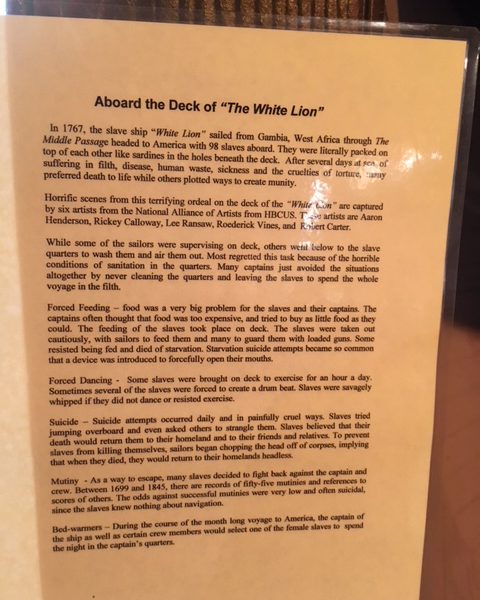

They walked pass the bookstore that showcased posters of Michael Jackson, handcrafts and books by black authors, including a seven-year-old who wrote six books, and many published with Moore’s help. Past the bookstore is a replica of The White Lion, a Portuguese slave ship that carried as many as 98 slaves on a trip. There the elementary schooler stopped to stare at the shackled figures stacked side by side on the ship. A moment later, adjacent to the ship, his mother read the poster with the names, ages and dollar value of blacks who were being sold. On it was a seven-year-old girl.

“How sad,” she said.

Moore concurred. “How could a seven-year-old cope with life after watching her parents sold and knowing she will never see them again in life,” he said. “It doesn’t get much sadder than that.”

The reactions vary, but for Moore, perhaps the most memorable, was a young white girl who burst into tears. She was the daughter of a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Father and daughter fought because of their opposing views of black people.

“’He would talk about killing n*****s and on Sunday go to church because he was a minister,’” she told Moore. She said if it wasn’t for her mother he would have killed her.

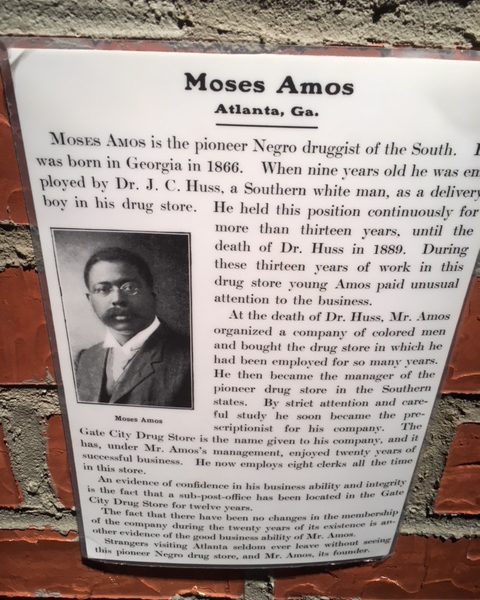

As the family continued, they came across the story of Moses Amos, the first black pharmacist in Georgia and a model of his store, which was later bought and became the Yates & Milton Drug Store.

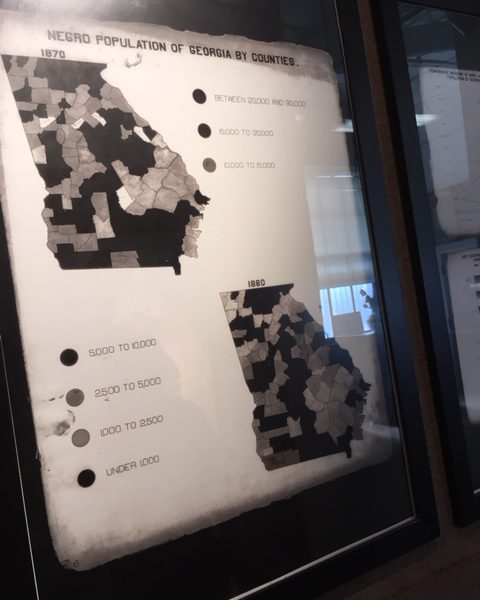

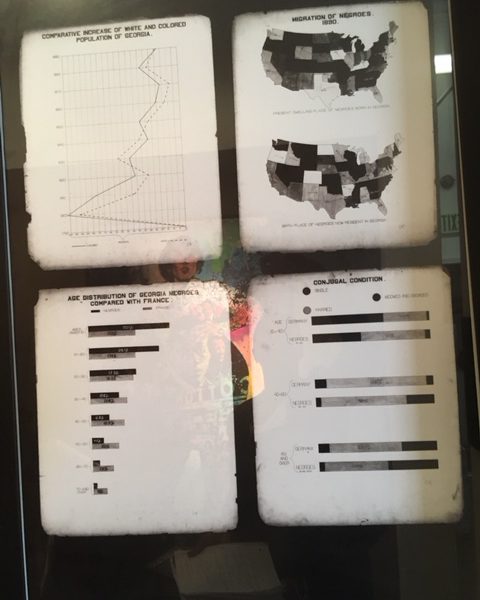

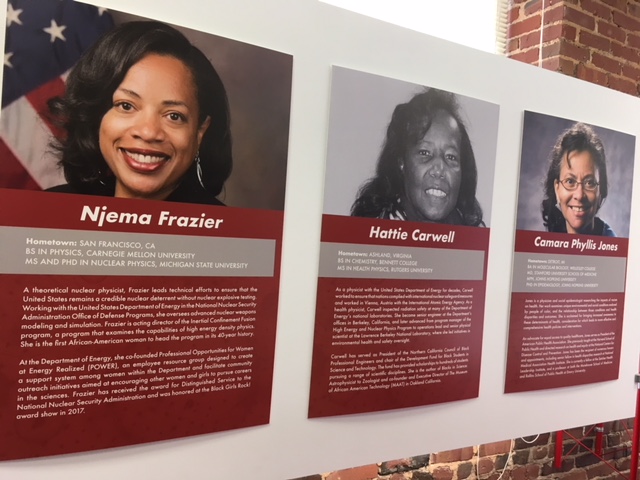

They would then see the museum’s two permanent exhibits: Women in Stem, which honors women who made contributions to Stem Cell research and W.E.B. DuBois’ award-winning, The American Negro. He also did, the Georgia Negro, which include dozens of photos that reflect black life in Georgia in the 1900s. They take up both sides of the museum’s walls in the hallway.

Those who take the tour are also treated to two short documentaries produced by Moore: The Journey, which was narrated by Ossie Davis. The film takes its viewers on a journey through ancient African civilizations to the swearing in of the 44th president of the United States of America, Barack Obama. Then there is Sweet Auburn, which was narrated by Cicely Tyson and Julian Bond. It tells the rich history of Auburn Avenue and explains why Fortune Magazine called it “The Richest Negro Street in the World” in 1957.

The museum, which is open Tuesday through Saturday, operates with three staff members, two college interns and volunteers.

“It’s been a struggle financially just to keep the doors open,” Moore said.

But, he said his is not the only one. Black museums are dying. Some have had to close their doors while others cut back their staff. Apex has survived through contributions from private donors and the board members as well as with revenues from tours and the parking lot, Moore said.

“For whatever reason, these African American museums are not being funded so the doors can’t stay open,” said Dr. Latangela Crossfield, a friend of Moore’s and a longtime supporter of the Apex.

Crossfield lived in Atlanta for more than 20 years before she found out about the Apex museum. Then a student, Crossfield needed help filming a documentary and someone recommended Moore. She met him at Apex and he gave her a tour.

“I was impressed in that I had never gone to an African American museum,” Crossfield said. “He sacrificed everything to make sure it happened because a lot of it was his money.”

Crossfield started volunteering at the museum and did so for about four or five summers. After she graduated, she continued to volunteer and still does when she’s needed. And, so she was one of the architects of the 40th Anniversary Celebration, which was paid tribute to the Harlem Renaissance. Pictures portraying that era have temporarily replaced pictures from The Georgia Negro and will remain in the museum until the end of the month, Moore said.

“Everyone doesn’t tell African and African American history the same,” Crossfield said. “It’s important that we all know our history and know the unadulterated truth of our history.”

And the Apex provides that truth, Crossfield said.

“We don’t get taught this in school,” said Crossfield, who received a doctorate in humanities with a concentration in African American history. “There were a lot of omissions. I’m just grateful that someone had picked up this torch and made sure the world had access to it,” Crossfield said.

-

Featured12 months ago

Featured12 months agoArkansas Sheriff Who Approved Netflix Series Says He Stayed ‘In His Lane’

-

HBCUS12 months ago

HBCUS12 months agoSenator Boozman Delivers $15 Million to Construct New UAPB Nursing Building

-

News12 months ago

News12 months agoMillions In the Path of The Total Solar Eclipse Witnessed Highly Anticipated Celestial Display

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates