Featured

100 Years Later, Why Don’t More Americans Know About the Elaine Massacre

A young woman sat near the door of the coffeehouse with its high ceilings and brick walls as night gathered, listening intently to the horror the speaker described. Clarice Abdul-Bey first heard the story of the Elaine Massacre of 1919 from her grandfather who fled the area with his parents and moved to Chicago. She, her husband, and son arrived at the coffeehouse in Pine Bluff, Arkansas after attending a park dedication earlier in Elaine.

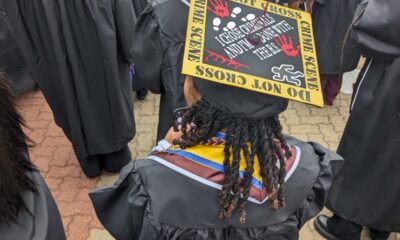

The 100-year commemoration of the tragedy in Elaine, Arkansas was marked with ceremonies around the state over the weekend. What occurred in the small eastern town in the Mississippi Delta is a reminder of a brutal era in American history that when mapped on the nation’s historic timeline was not that long ago and offers a solemn reminder of the tragic consequences when racism is left unchecked.

“Events like this don’t just happen out of the blue, they happen in a context,” Dr. Kevin Butler, a sociologist, told the small crowd who assembled for an evening memorial service for the victims. “There has to be a culture that tells people this is an appropriate way to react. A culture that tells people you can do things like that and get away with it.”

It was September 30th, 1919 and a group of sharecroppers, who hired an attorney and expressed an interest in joining a union to receive their fair share of the money the white landowners made from the crops cultivated by their labor, were meeting at a church. The meeting had been leaked by a “friendly Negro” and several white men sat outside. One of the men fired into the church. Fire was returned and a white man was killed. Over the next few days, whites raged throughout Phillips county, claiming they were the targets of the sharecroppers. They killed, some historians say, over 200 black men, women, and children. No one was ever charged with their deaths.

Twelve black men were arrested for the murders of the five white men who died. They became known as the Elaine 12. They were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by an all-white jury.

“The person who did most of the work and got very little credit for it was Scipio A. Jones, an African American attorney in Little Rock and with the help of the NAACP, they were able to take the case to the courts,” said Butler.

Jones appealed the verdicts, and the case wound its way through the judicial process to the Supreme Court which ruled that the trial violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision was a landmark ruling because in Moore v. Dempsey the High Court declared that state rulings could be challenged in federal court to see if defendants had been denied their constitutional rights.

As the 200 candles lit in memory of the victims began to burn low in the coffeehouse, the reticence to share personal stories punctuated with Jim Crow-era injustices melted.

Verna Perry pointed out that sharecroppers in other states also suffered mistreatment. Her dad was sent to reform school as a 16-year-old because he tried to defend his family from the predatory financial tactics of the landowners.

“The story was that he hit a white farmer in the head because he tried to make his mother and his siblings stay on a farm and continue to farm,” Perry said. “They had been willed 40 acres to build a house on, and the guy didn’t want them to leave.”

The family managed to leave and farm the land they inherited.

According to Butler and other scholars, the landowners were often unscrupulous in their dealings with sharecroppers. In many instances, the landowner also owned a store where sharecroppers purchased essentials.

“They had to get it on credit because they didn’t get any money until the end of the year,” Butler stated. “At the end of the year when the money came in, the store owner got his money first. They would say ‘Add up all the stuff.’ They’d add that up plus interest, and the interest was high. It could be as high as 50 percent. Add up all that, and they’d say, ‘You didn’t make any money. You still owe me.’”

Those were the unfair circumstances that stole the hopes and dreams of many sharecroppers and the reason the men in Elaine dared meet that fateful evening in late September. They wanted a fair labor arrangement. One hundred years later their courage in the face of unparalleled violence is remembered.

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoCalifornia Is the First State to Create A Public Alert for Missing Black Youth

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoAfrican American Leaders Stay the Course Amid Calls for President Biden To Bow Out of Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoThe Debate Fallout Lands on Both Candidates

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoPresident Joe Biden Decides to Withdraw from the Presidential Race

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoPresident Joe Biden Describes Shooting of Donald Trump As ‘Sick’

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoIn One of His Final Speeches as President, Biden Says It’s Time for ‘Fresh Voices’